Fashionable, wealthy and influential, Elle editor Jean-Dominique Bauby seemingly had it all. Yet, when he suffered a stroke driving in his convertible in the middle of the French countryside, leaving his beautiful country home, one wonders if the damage he eventually suffered could have been averted if he had been closer to immediate medical assistance. We meet Bauby when he first wakes up in the hospital, where he discovers he has been in a coma. The doctors' standard questions soon turn to concern as the extent of the damage Bauby has suffered becomes apparent. He is diagnosed with Locked In Syndrome – a rare condition in which the brain retains all cognitive function but is unable to communicate with the rest of the body – and the once worldly Bauby is now confined to a wheelchair, unable to even speak.

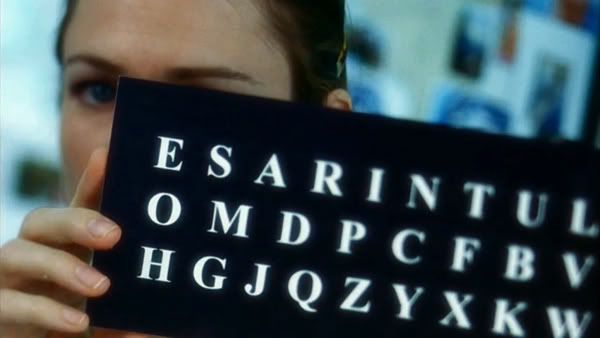

The masterstroke of Julian Schnabel’s film, is that it refuses to stay confined by Bauby’s physical condition. Based on the titular memoir by Bauby - composed entirely by communicating to his speech therapist by blinking his left eye to identify letters as she reads them down from a chart in order of popular usage - Schnabel’s film pushes its setting far beyond the hospital doors, capturing the endlessly fertile thoughts spinning in Bauby’s head. While the film does focus on Bauby’s health and his care, celebrating his struggle and accomplishment in penning the novel, it never flinches from presenting his troubling relationships with the women in his life or the seemingly vacuous nature of this job at the magazine. Both before and after the accident, Bauby is presented as smart, sarcastic, funny, a jerk and a warm-hearted friend. We see him for everything he is from a dedicated son in the moving and heart wrenching scenes with his father (played magnificently by Max Von Sydow), to a callous, selfish man as he continues to juggle relationships between his lover and his wife, even from his hospital bed.

Largely filmed from Bauby’s point-of-view perspective, it’s no surprise that Julian Schabel comes from an art background. He finds compelling and beautiful ways to both capture to the terror of Bauby's condition and the beauty of his imagination. Using his painter’s eye, and working alongside noted cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, The Diving Bell & The Butterfly is a film that – like its subject – uses its limited resources to maximum effect. It refuses to be bound by conventions, and leaps boldly and beautifully to piece together the memories of a decadent life that finds its meaning in the gravest of tragedies.